|

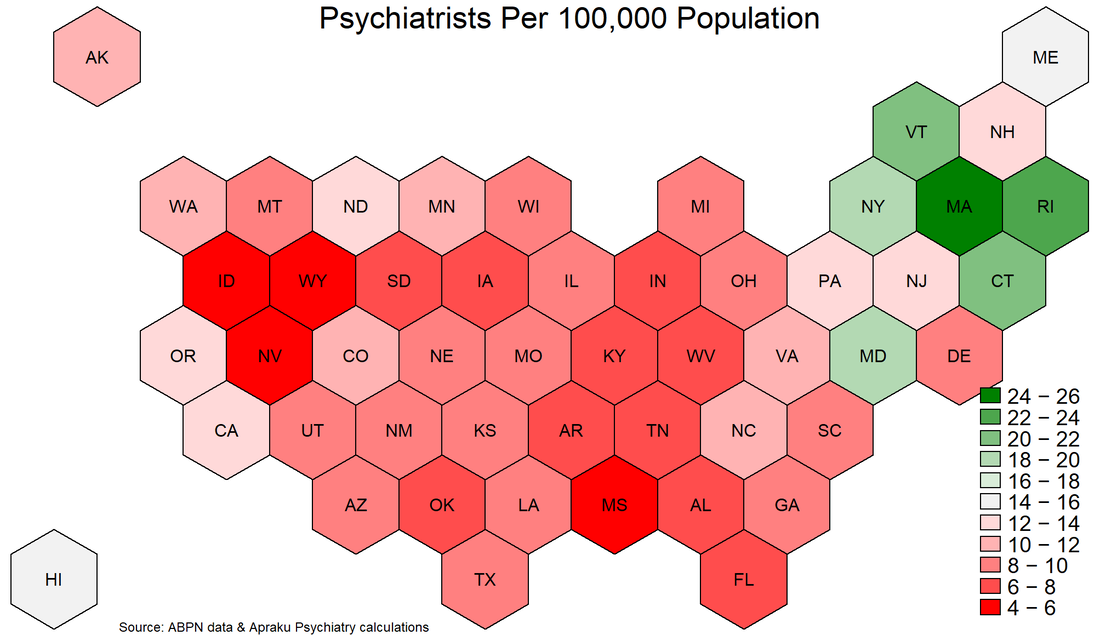

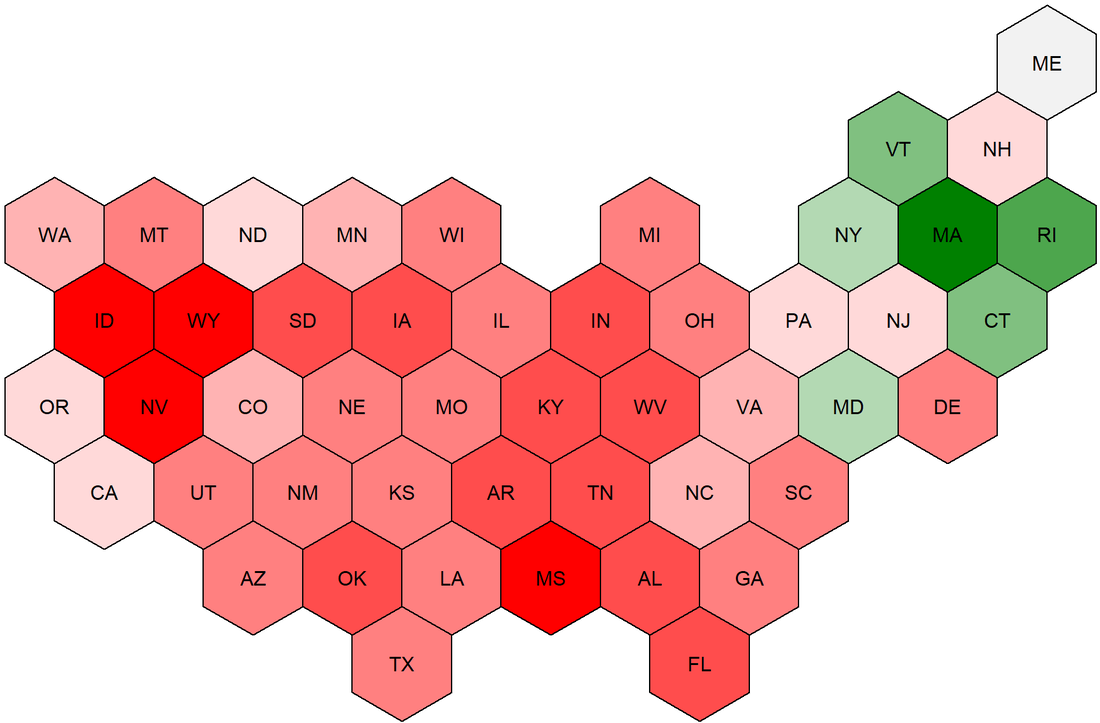

The United States has a severe and growing shortage of psychiatrists. While demand for mental health services is rising, the pool of psychiatrists is shrinking: graduating residents are too few to replace new retirees. The Department of Health and Human Services estimates the shortage of adult psychiatrists to reach 12,500 by 2030, representing nearly 50% of psychiatrists nationwide. Unfortunately, the current situation is perhaps even worse than described by the DHHS. For starters, the DHHS assumes that all psychiatrists work until age 75, which seems overly optimistic about enthusiasm for late-life work. Moreover, the DHHS report uses a dataset maintained by the American Medical Association, which records physicians' self-designated primary specialty. However, self-designation does not necessarily mean that a physician has expertise or Board certification in psychiatry. Finally, AMA records are often not kept up to date by physicians, as this is not required for licensing purposes. To better gauge the availability of qualified psychiatrists, we can use data from the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Active certification by the ABPN is the gold standard in psychiatry. We further restrict the data sample to Board-certified psychiatrists who were initially certified between 1988 and 2019 (psychiatrists certified before 1988 are assumed to have retired, consistent with a retirement age of 65). The ABPN data indicate that there are just over 35,000 Board-certified psychiatrists of working age in the US. This stands in contrast with the figure of approximately 42,000 estimated by the DHHS, suggesting that the current shortfall in psychiatrists may be twice as large as previously reported. Most of the discrepancy arises from DHHS's assumed retirement age of 75 rather than 65, while the remainder comes from the fact that the DHHS relies on physicians' self-designated specialty, rather than their Board certification. The ABPN data also contain information on the primary city in which psychiatrists practice. This allows for in-depth analysis of geographic dispersion in availability. As a first step, we can plot the state-level distribution of psychiatrists per 100,000 population (see graph below). According to the DHHS, demand for psychiatric services requires a supply of approximately 15 psychiatrists per 100,000 population. Just six states - MA, RI, VT, CT, NY, MD (in descending order) - comfortably exceed this threshold; the vast majority of US residents therefore live in a state in which the psychiatrist-population ratio is inadequate according to DHHS estimates. Worryingly, 14 states have a psychiatrist-population ratio which is less than half of that which the DHHS deems adequate. What can society do about this psychiatry shortage? To answer this question, it is important to distinguish two aspects of the problem: aggregate shortage and geographic dispersion.

To address aggregate shortage, there is only one answer: get more psychiatrists! Over the long run, an expansion in residency training programs would help to increase the rate at which retiring psychiatrists are replaced. In the shorter-run, a more liberal immigration policy and licensing regime with respect to foreign-trained psychiatrists would help alleviate scarcity. These solutions are preferable to lowering standards of care, for example by expanding the ability of nurse practitioners to practice independently. In general, foreign-trained psychiatrists follow a more rigorous curriculum than US-trained nurse practitioners. There are multiple solutions to the geographic dispersion problem. The most readily implementable involves greater adoption of tele-medicine, as practiced by Apraku Psychiatry, which can alleviate within-state scarcity. Unfortunately, state-level regulation of physician licensing impairs the ability of tele-medicine to alleviate cross-state scarcity, although the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact may be somewhat helpful in reducing frictions in this respect. In the longer-run, a strategic geographic reallocation of psychiatry residency programs could help to expand coverage in under-served areas. Some provisions in the Affordable Care Act (2010) went in this direction, but the analysis shown here underscores the need for a more extensive overhaul. Comments are closed.

|

Copyright © Apraku Psychiatry 2024